Quick! Describe a motivation upon which you can build a memorable story. Plug it into the character you’ve been thinking about for ages. Does it read well? How does your character come to life? It’s not as simple as it seems, is it? The motivation has form in your thoughts, but it doesn’t seem convincing on paper. Why?

One thing is certain: what we “see” in our minds is transient. Unless we can send the thought or image down our brain stems, over our shoulders and along our arms, through our fingers to the blank paper or canvas, we reveal that we don’t really understand what we are trying to communicate. C.S. Lewis put it this way:

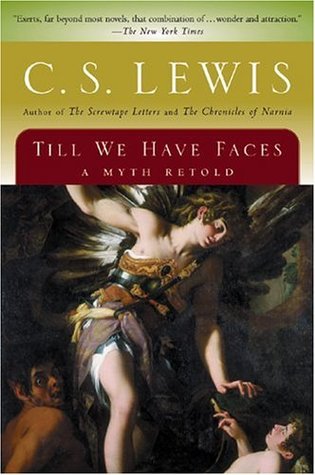

“Till the word can be dug out of us, why should they hear the babble that we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?”

SO – how do we go about solidifying our thoughts into communicable art such as stories, illustrations, film and games?

We develop and hone the writer’s primary toolset: our powers of observation, critical analysis and synthesis. It has to start here.

When we want to dress a character with behaviors and motivations, we watch people in the real world. Not superficially – but with our hearts, minds, and souls. We take emotional chances by making dangerous leaps toward understanding how we fit into our relationships with others. We examine our own motivations and responses in context of those from people around us. We run into uncomfortable, sometimes painful, self-realizations. We gain perspective – and, in return, perspective gives us words.

Now – now we can develop some character motivation. It will be Real. Honest. Convincing.

This post is the first in a series I am writing on my observations of human motivations and how they fuel character development, goals, and the stories in which they prevail. Let’s begin with…bitterness.

Bitterness is insidious. It comes quietly into our lives, borne on the hot, sticky wind of grievance. Its seed falls into the unguarded cracks and crevices of our souls – sending toxic roots deep into the dark, unnoticed places of our being.

Suddenly, a sprout breaks through to our consciousness. It flowers, and we nurture the thing because weed flowers can be beautiful – especially so when they satisfy our need for justification. Before we know it’s happened, the lovely flower becomes an ugly seedhead that scatters itself across our battered souls with every new ill wind that blows against us. Our inner gardens are overtaken by weeds – we don’t seem to recognize ourselves anymore. We don’t know who or what we’ve become – we only know that we need a master gardener to work the miracle that will turn our cracked, dead soil into the deep, fruitful loam we remember.

Well – we need a gardener or a fabulous, sure-fire plot for revenge.

Many famous literary and film characters have been motivated by bitterness – protagonists who get that miracle, or antagonists who want revenge. (Sometimes vice versa!) Bitterness is a believable motivation – we’ve all experienced it in ourselves, or been recipients of its poison. We know it’s real. We recognize it in the suppressed anger of sarcasm, or the faithless cynicism of lost hope, lost joy.

Good stories are like our lives – full of subtlety until passions erupt from the places in us that we thought were well hidden…under control. The Shadow archetype is an intimate life companion to all.

Hurry! Push that thing back into the depths from which it came…or let it play out in a dramatic, believable story of becoming. Lots of great literature rests on such plots.

C.S. Lewis retold the myth of Cupid and Psyche as a tale of the bitter struggle between two sisters, a beautiful girl whose nature represented the sacredness of love, and a plain girl whose nature represented the profane character of love marred by jealousy. It’s a profound tale of completion and maturation. The subtle nuances of Lewis’s understanding of, and familiarity with, bitter jealousy make the story almost uncomfortable to read. It strikes close to home. Who knows if the great author felt this himself, or merely observed it on the playgrounds of life. Either way, the power of the story derives from Lewis’s willingness to explore something destructive, ugly…shadowy.

The novel is bittersweet by the end of the journey. The plain sister is more beautiful in her wisdom than the external beauty of her sibling. That’s another truth in writing that we must both observe and internalize. All does not always end well in real life – neither should it in the stories we tell, if we want to connect with our audiences. What we can offer is…lessons learned.

Life truth for Lewis’s readership: Real Love (and not just the romantic kind) is not the product of things that are skin deep. It happens when soul recognizes soul, hearts find unity…minds elope on the adventure of life. It comes from connection. E.E. Cummings put it this way in the first part of one of his poems:

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

What do you think he means by this? Is the “kiss” real, or does it describe the kind of “knowing” only experienced on the level of the soul? Is the soul where the “feeling” originates? Is “syntax” about love grammar…or could it be the physical realities of life that pale to insignificance when love is met?

Intangible, noumenal human experiences such as love and bitterness must be observed and carefully analyzed by the writer. Buried within them are the motivations that fuel life. Without authorial understanding, a character’s motivation loses its life force – like an image frozen in time on photo paper. It becomes a superficial suggestion, syntax,…not enough to push a story into being.

Here’s an idea: get a simple notebook that fits in your pocket or bag. Carry it with you everywhere and record your observations of human behavior and motivations. Don’t forget to synthesize (reconcile) your own experiences in the body of these observations. Later, test how these observations look on your characters!